Following the American Revolution, a new business system emerged encouraging the “virtuous and independent citizenry” of this new nation to pursue new entrepreneurial opportunities.[1] This entrepreneurial energy in New Hampshire, combined with the ready availability of water-power, contributed to dramatic economic growth. In fact, by 1880, there were approximately 900 water-powered mills in New Hampshire. According to historian James Garvin, in light of the state’s abundant water resources, New Hampshire became the most industrialized of the three northern New England states. Garvin also noted that by 1870 the region’s industrial sector outpaced its agricultural endeavors. On a national level New Hampshire was one of the “most heavily industrialized regions in the nation in relation to the size of the population.”[2]

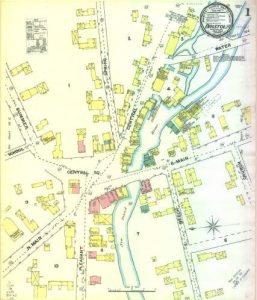

In 1819, the southerly portion of the town of Bridgewater combined with the northerly portion of the town of Hill to form Bristol. At the time of its charter Bristol was considered one of the smallest towns in New Hampshire in area, yet its water resources created natural advantages that would forever change the community’s landscape. The water-power resources along the Pemigewasset and Newfound Rivers (flowing from Newfound Lake) offered a plethora of opportunities for new economic expansion and prosperity. Moreover, the Newfound River falls more than 241 feet in two miles, adding significantly to the available water-power for manufacturing interests. Where water-power potential was sufficient to support factories, numerous investors organized to build dams and canals to serve a number of factories clustered within a small area, near the water source, and often subject to flood damage. [3]

The growth of manufacturing in Bristol forever changed the surrounding environment with the building dams and mill ponds. Add to this the opening of roads and the arrival of the railroad, and Bristol soon became a center for trade, resulting in the creation of ancillary businesses, and an increased population, both necessary to support continued economic growth. Much of Bristol’s early development occurred within walking distance of manufacturing entities and transportation corridors. Merchants established a post office and stores selling dry goods, clothing, millinery, and shoes in the heart of this growing community. Soon taverns, hotels, and a bank opened to enhance continued economic progress. By the early 20th century, the center of Bristol was a hive of activity and prosperity. Unfortunately, with the shift to new forms of power generation, the ebb and flow of rivers became no longer essential to manufacturing. With the advent of new technologies, factories were relocating, no longer bound by the need for water-power. The once-booming economy in Bristol, like so many other industrial communities in New England, struggled to survive amidst economic downturns and new business strategies that evolved with the transition from a producer-dominated economy to a consumer-oriented society. [4]

Today, signs of Bristol’s manufacturing heritage are visible throughout the Central Square Historic District, providing a sense of history and a perspective on the past. Through adaptive reuse many of the buildings continue to contribute to the region’s economy. Reminders of the past often evoke a sense of pride and belonging that enables us to gain an understanding of place or neighborhood and harness that understanding in order to build a viable future.

Please explore twelve of historic Bristol’s sites and discover the character of this special community.

[1] Mansel G. Blackford and K. Austin Kerr, Business Enterprise in American History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1994) 43 – 63.

[2] Robert B. Gordon and Patrick M. Malone, The Texture of Industry: An Archaeological View of the Industrialization of North America, (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1994) 99. James Garvin, Instruments of Change: New Hampshire Hand Tools and their Makers, 1800 – 1900 (Canaan, NH: Phoenix Publishing 1985) 3, 15, 20.

[3] State of New Hampshire Town Charters, Vol. XXIV, 1894, 262. The Granite Monthly, Vol. v, No. 8, May, 1882, 262 – 272. Hamilton Child, Gazetteer of Grafton County, N.H. (Syracuse, NY: H. Child, 1886)

[4] Blackford, Business Enterprise, 227 – 259.